Loneliness in Aotearoa

When choosing this year’s Mental Health Awareness Week theme, the team at the MHF wanted to highlight the importance of connecting with others for our mental health. Taking time to kōrero with friends and whānau is one major way we can boost our own wellbeing and the wellbeing of those around us. It’s also a great way to combat something that will affect many of us throughout our lifetime - loneliness.

Loneliness is something many of us will experience, and yet it is often something people feel ashamed to talk about. We spoke to Holly Walker, deputy director of the Helen Clark Foundation and loneliness researcher, about her recent report into loneliness in Aotearoa, Still Alone Together.

“We need each other. We're social animals - that's how we’re wired. Loneliness is actually a normal human emotion that we will all experience at different stages of our lives, but it's only really supposed to be temporary.”

“Loneliness itself is not a mental health problem, but prolonged loneliness can be a significant risk factor for developing poor mental health. It has profound impacts on mental health and wellbeing to stay in that state for a long time, so it can contribute to depression and anxiety. There's also all kinds of physiological impacts. It messes with your hormones, it messes with your sleep. It can elevate your blood pressure and can increase your risk of heart disease.”

Holly’s research began looking at loneliness from an urban design perspective - thinking about the ways public places encourage or discourage social connection. However, the shape of the research quickly changed after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It suddenly became a whole lot more urgent and pressing because we were all in Level Four lockdown and in a state of enforced social isolation.”

Still Alone Together is a response to the original Alone Together reporton lockdown loneliness published last year, which found that while many groups bounced back from adverse mental health effects of 2020 lockdowns, there were still some groups much more likely to experience loneliness.

People living with disabilities were four times more likely to report feeling lonely than able-bodied people, while unemployed people, people on low incomes, sole parents, new migrants, people of Asian descent and young people aged 18 to 24, were also all more likely to experience loneliness.

For many of these groups, the extra support they may have felt extended to them in Level 4 quickly dissipated once New Zealand began to return to a relative normal.

“One of the things we found in our second report was that self-reported loneliness for many of these groups actually increased after the lockdown last year.”

“Our hypothesis is that during the lockdown we were all very conscious of social isolation and made quite a considered effort to check in with people who lived on their own, older people, disabled people - to stay connected, drop off groceries, have Zoom conversations… When the lockdown ended and most of us went back to our normal lives, a lot of that support fell away. And so for people who are already isolated, actually that period of return to ‘normal’ after lockdown was even more lonely.”

To better support these groups, it’s important to keep reaching out to others post-lockdown, to keep offering that same level of connection and support as we move back down alert levels.

“I think it’s important if we're in the position of being able to reach out to others to do that, even when we're busy and back to our regular existence.”

However, while individual-to-individual support is incredibly important, there are also a number of external factors in our society that contribute to increased rates of loneliness in certain groups.

“It’s pretty clear these issues cannot be solved with individual actions, as important as those are. We’re talking about what policies the government can adopt to create the conditions that make it easier for social connection to thrive.”

Still Alone Together outlines six overarching recommendations that, if put in place, could significantly impact the prevalence of loneliness in Aotearoa. These are:

1. Make sure people have enough money.

“Poverty is a huge risk factor for loneliness. If you have a really low income, a lot of your time and mental energy and headspace is spent in a state of toxic stress, trying to solve where your next bill payment, your next grocery shop is coming from. You don't have a lot of time and headspace for meeting your own self-care needs, your social needs, connecting with other people.”

2. Close the digital divide.

“In lockdown, that digital connection is a really important tool, but it actually isn't available to everybody. There are still quite a large number of people in New Zealand who don't have a regular internet connection or an internet enabled device, or they have one that's shared between a lot of different household members.”

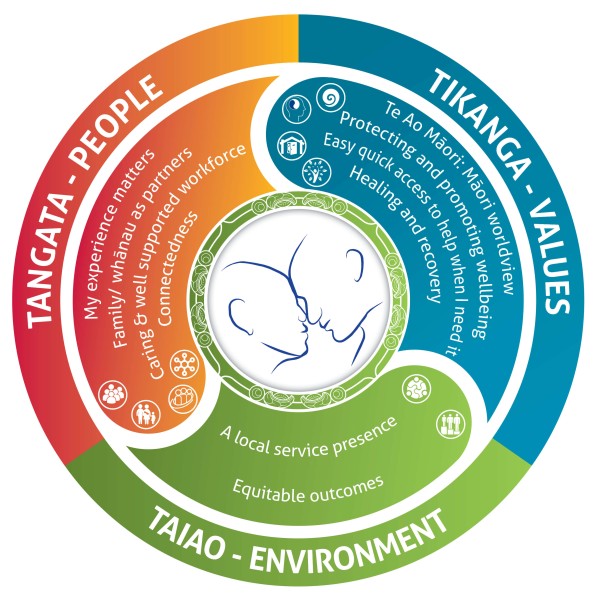

3. Help communities do their magic.

“Where the rubber hits the road for a lot of people is actually in the community in which they live, whether that's their geographical community, like the neighborhood or community of interest, or as part of a cultural group, a sports team, a church, a school community…”

“Investing in community-led development and adequately supporting and funding community organisations is important, especially disability spaces that are accessible.”

4. Build friendly streets and neighbourhoods.

“Looking at how we could actually design, for example, housing developments to facilitate social connection. We looked at emerging Maōri housing models that put a lot of emphasis on collective spaces, community spaces, shared places for shared kai for communities to come together, outside spaces where kids can play and be supervised by parents and guardians from the whole community.”

5. Prioritise those who are already lonely.

“Targeting services and supports to those we know who are more likely at risk, because we've got really good data about who those people might be.”

6. Invest in frontline mental health services.

“For those who are spending a long time feeling lonely, who developed that kind of chronic loneliness, and it is impacting on their mental health, they need to be able to access services and support that is affordable and immediately available.”

For many of us, loneliness will be something we experience at least once during our lives. The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdowns have exacerbated this for some, while for others it is the return to relative ‘normal’ that signifies a falling away of support and a return to chronic isolation.

Changes at a policy level are obviously necessary to create real, positive change for many people feeling isolated and lonely in Aotearoa. While we should continue to advocate for these, we cannot lose sight of the tangible impact we can make right now, just by making the effort to reach out to one another.

“We should still encourage and support people to do what they can in their individual lives.”

“Whether that's someone who's feeling lonely, making that step to sort of reach out and talk to someone else and tell someone, talk about how they're feeling, but also for people who may not be experiencing loneliness to be aware of others who might be and make a conscious effort to connect.”

Now more than ever, we must continue to reach out, connect, listen, support one another, and take time to kōrero. Paired with the policy and advocacy work undertaken by organisations such as the Helen Clark Foundation and the Mental Health Foundation, these simple actions can make a real, tangible difference in the mental and emotional wellbeing of ourselves and the people around us.

Iti te kupu, nui te kōrero. A little chat can go a long way.

For more information on how to get involved in MHAW, including great resources to use at home, head here.